Chelmsford: Trials and Executions

July 17, 1645.

A staggering twenty-nine women were set to be tried at the Chelmsford Assizes on July 17, 1645. This number had shrunk from the original thirty-six women imprisoned on charge of witchcraft: four women died in Colchester Castle before their trial, two had their trials postponed, and Rebecca West had been set free after agreeing to testify against others.

Chelmsford was overwhelmed by the unprecedented number of witchcraft cases to be considered. Worse, the ongoing Civil War had disrupted the routes assize judges travelled, meaning that the trials would be overseen by Robert Rich, the Earl of Warwick, an impressive military figure but one with little legal expertise. Warwick and the county magistrates not only had the witches to try, but suspects for other crimes as well. All were to be tried on July 17, meaning some had their fates decided in mere minutes.

Elizabeth Clarke, the first accused witch, was originally questioned on suspicion of bewitching the tailor John Rivet’s wife. However, she was not indicted for this, but on two other charges: bewitching and killing the infant son of Richard Edwards, Chief Constable, and his wife Susan, step-sister to Matthew Hopkins (witchfinder), as well as for keeping imps. Hopkins is known to have testified against Clarke and it is likely the Edwards did as well as they are listed as witnesses on her indictments. Elizabeth was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

Rebecca West was coerced into testifying against her own mother, Anne West. Anne was indicted for bewitching and killing a yeoman’s son and for keeping imps. Unusually, the magistrate Sir Thomas Bowes testified against her —this was an uncommon practice, especially as the evidence Bowes presented was not his own but that of another witness not present in court. Bowes had previously arrested Anne for witchcraft in 1642, suggesting he still held a vendetta against her. Anne was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

Nineteen of the twenty-nine women were sentenced to hang. Fifteen were executed the following day at Chelmsford in what was then England’s largest mass execution of witches (a record that would be broken the following month in Suffolk at the Bury St Edmunds’ trials). The other four were executed at Manningtree two weeks later on August 1.

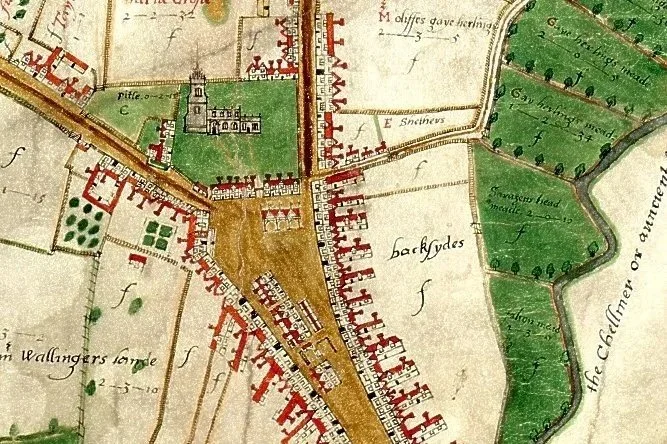

This 1591 map depicts the Chelmsford Cathedral and below it the town square including the Shire House where the witches were imprisoned and tried.

It is unknown exactly where the executions took place.

There is today an interpretive plaque located in Admirals Park in memory of the executed.

The women were likely buried near the place of execution in unmarked graves.

Today.

Most of the original buildings no longer exist, but the town square layout is still the same.

The Shire Hall that stands today (pictured) is not the original building, but was built in 1791 near the original Shire House. It is no longer in use.

Crowds would have gathered in the market to try to catch a glimpse of the witches. Trials and executions were a form of public entertainment, and a mass trial of witches would have drawn particular excitement.

The current exterior of Chelmsford Cathedral is a mixture of medieval and Victorian architecture.

While not directly tied to the trials, it towered over the square and would have been one of the last sights the women saw on their way to the gallows.

One woman marked for execution, Margaret Moone, collapsed and died before reaching the execution site, probably from fear. Her condition was presumably worsened by the jeering crowd.

The Museum of Chelmsford features further displays on the town’s history.

Further reading.

A true and exact relation of the severall informations, examinations, and confessions of the late witches, arraigned and executed in the county of essex. (London, 1645)

C.L’Estrange Ewen, Witch Hunting and Witch Trials (London, 1929)

Malcolm Gaskill, Witchfinders: A Seventeenth-Century English Tragedy (Harvard University Press, 2005)

Marion Gibson, Witchcraft: A History in Thirteen Trials, (Simon & Schuster UK, 2024), ch 5

Frances Timbers, “Witches’ Sect or Prayer Meeting?: Matthew Hopkins Revisited”, Women’s History Review, vol 17 (2008)